Marysia Stronska was thirteen years old when her family was deported from Poland to Siberia in 1940. Her family history has many parallels to that of my grandmother’s, going through a similar migration through Siberia, Kazakhstan, and - after her father died in Uzbekistan, and was buried in the same cemetery as my great-great-grandmother - eventually ending up in a refugee camp in Uganda. An outspoken and tough young woman, she often had trouble with authority, whether in the Siberian forced labour camp she was sent to at thirteen, after being caught making a joke about the Soviet Union, or while challenging the “toughness” of her Polish boy classmates in Uganda.

Marysia (far right) at a Polish refugee camp in Masindi, Uganda with friends.

Like my grandmother, Marysia ended up in England when the refugee camps were closed, where she frequently had to stand up to xenophobic comments from her new neighbours and colleagues. She eventually married and settled in Montreal, Canada, where she went on to start a family and become a natural leader within the Polish community. She was not only a Polish teacher, but an organizer of Polish-African refugee reunions, and very active within the Polish church community. Having survived everything she went through during WWII and aftewards, she expresses a perpetual obligation to do something useful with her life.

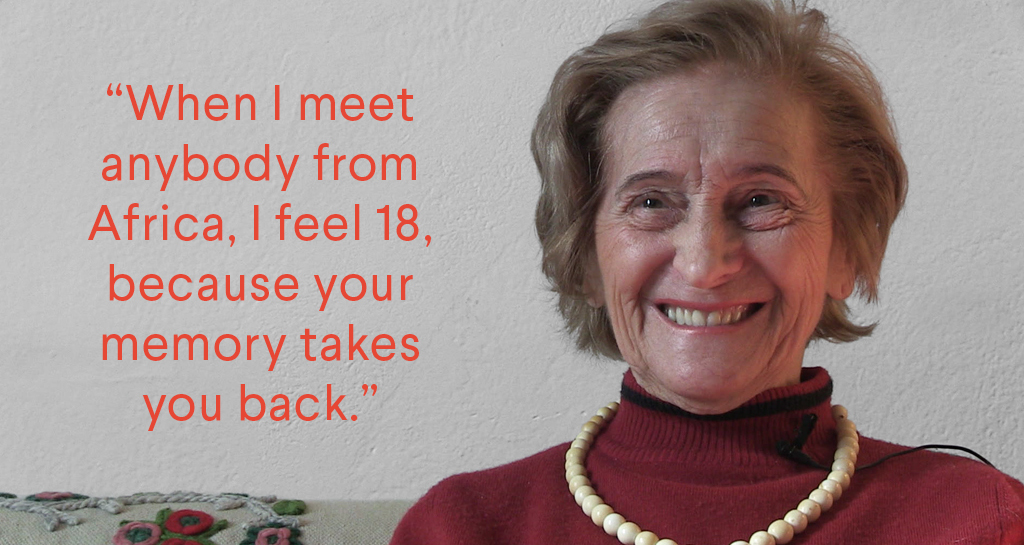

Today, at ninety years old, she is philosophical about her time as a young refugee. Despite extreme hardships that she survived in Siberia and the Soviet Union, she doesn’t resent the Russians, stating that the people themselves were actually quite hospitable, considering how little they had. Her opinion of Churchill and Britain however is not so rosy. She felt betrayed as a young woman when the promise of going home vanished when England agreed that Poland would fall under Soviet control. Although she has made Montreal her home, she maintains close connections with other Polish-African refugees around the world, and serves as an inspiration to her community through her resilience and strength in the face of profound adversity.